|

As early as 1974, a DARPA study was initiated and led by Ken Perko. He requested

White Papers from Northrop, McDonnell Douglas, Fairchild, General Dynamics

and Grumman, asking two questions: 1°) What were the signature thresholds

that an air vehicle would have to achieve to be essentially undetectable at

an operationally useful range? 2°) What were the capabilities of each company

to design and build an aircraft with the necessary signatures? Fairchild and

Grumman did not express any interest in the study. The General Dynamics response

emphasized countermeasures and had little substantive technical content regarding

signature reduction. Northrop and MDD responded indicating a good understanding

of the problem and some capability to develop a "reduced-signature" air

vehicle. MDD was also the first to identify what appeared to be the appropiate

RCS thresholds. In late 1974 DARPA awarded Northrop and MDD contracts of aproximately

$100,000 each to conduct further studies. These initial studies were classified "Confidential",

the lowest of three major levels of security classification: Confidential,

Secret, and Top Secret. In the spring of 1975, DARPA used McDonnell Douglas's

values (confirmed by Hughes radar experts) as the goals for the program, and

challenged the two participants to find ways to achieve them.

|

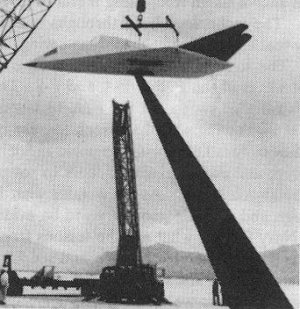

Northrop XST Powerplant: no data Date of design: 1975 In September 1975, Northrop and Lockheed's Skunk Works (McDonnell Douglas had fallen out of the competition) were asked to design a small prototype aircraft and build a full scale model for a "pole-off" at the RCS range at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, with the winner going on to flight testing. By now, the project's name had become the Experimental Survivable Testbed, or XST. Irv Waaland, a Northrop designer knew that Northrop had a problem. Northrop's analysts had concluded that it was most important to reduce its vehicle's RCS from the nose and tail, and the nose-on RCS (the view an adversary had in the critical head-on engagment) was more important than the rear aspect. Its XST design was a diamond with more sweep on the leading edges than the trailing edges. From the rear, it had low RCS as long as the radar was no more than 35 degrees off the tail. But the DARPA requirement treated RCS by quadrants: The rear quadrant extended to 45 degrees on either side of the tail, thereby including the parts of the airframe where the Northrop design's RCS spiked. Waaland could not solve the problem by increasing the sweep angle of the trailing edges, the aircraft would become uncontrollable. Northrop had an internal issue to deal with. "The level of security on the observables was higher than it was on the airplane," says Waaland, "and not too many of the airplane people were cleared into the [details of the low-RCS design theory]. It was a great source of frustration, because there was no ability to make compromises." This put Northrop at a disadvantage, because the program was all about compromise: to minimize RCS while attempting to preserve acceptable aerodynamics. the normally reserved Waaland recalls epic shouting matches in which he would question John Cashen (a Northrop electromagnetics expert) about some aspect of the mysterious electromagnetics. "You know just enough to be dangerous," was Cashen's usual retort. By now a change had crept into the program. Alan Brown traces it to the first Lockheed and Northrop 1/3 scale tests at McDonnell Douglas' Gray Butte RCS range in California's Mojave Desert in the December of 1975. (Lockheed tested the D-21 vs. "Hopeless Diamond" here because it did not have a range of it's own at the time.) The RCS numbers were not merely half of those of a conventional aircraft, but a hundred or a thousand times smaller, enough to make most radars useless. "People realized we had a tiger by the tail" says Brown. Throughout most of the testing, the competing contractor teams and their models were kept in isolation from each other, Temporary quarters were set up so that each team would have access to the range but could be kept apart from the other team. However, after most of the tesing was completed, each team was allowed to drive out on the range to view the other's model mounted on top of the 40 foot pylon. Technical performance, risk, cost, and schedule of the two competitors were very close. Therefore, choosing the winning team for PHASE II was somewhat subjective (and since then has been argued with). Technically, Lockheed's entry had a slight edge (based on the required quadrants). Overall, Northrop's XST was possibly stealthier than the Lockheed entry, but this conclusion is based on factors that weren't part of the DARPA requirements. Although both companies had developed special materials and construction techniques, the perception was that the Skunk Works had more experience with the use of these techniques on actual aircraft. The Skunk Works also had a proven record of accomplishing advanced, high-risk projects quickly under high security. These factors provided confidence that the Skunk Works could execute the XST program successfully. In April 1976 Lockheed was announced the winner of the PHASE I compition. Population: not built (full-scale mock-up only) Specs: unknown Crew/passengers: 1 (planned) Main source: http://www.f-117a.com/XST.html |

This website is conceived,

designed and maintained by BIS © 2006-2010 BIS Productions

Although every effort is made to make the information accurate, a mistake is

always possible.

Feel free to send an e-mail to correct or update any page of this site.